A Chairde,

We are now in the season of Lughnasa or Lúnasa in modern Irish. Lúnasa is the Gaelic word for the month of August. In the traditional Gaelic seasons, Lughnasa came after ‘Hungry July’ (Iúil an Ghorta), when food was scarce before the harvest. The spirit of Lughnasa invited people to embrace life with open arms, to dance with unbridled joy and hopeful abandon. This season, both historically and today, serves as a time to honour the cyclical nature of the seasons, reap the invigorating energy of creativity, and acknowledge the fruits of patience and hard work.

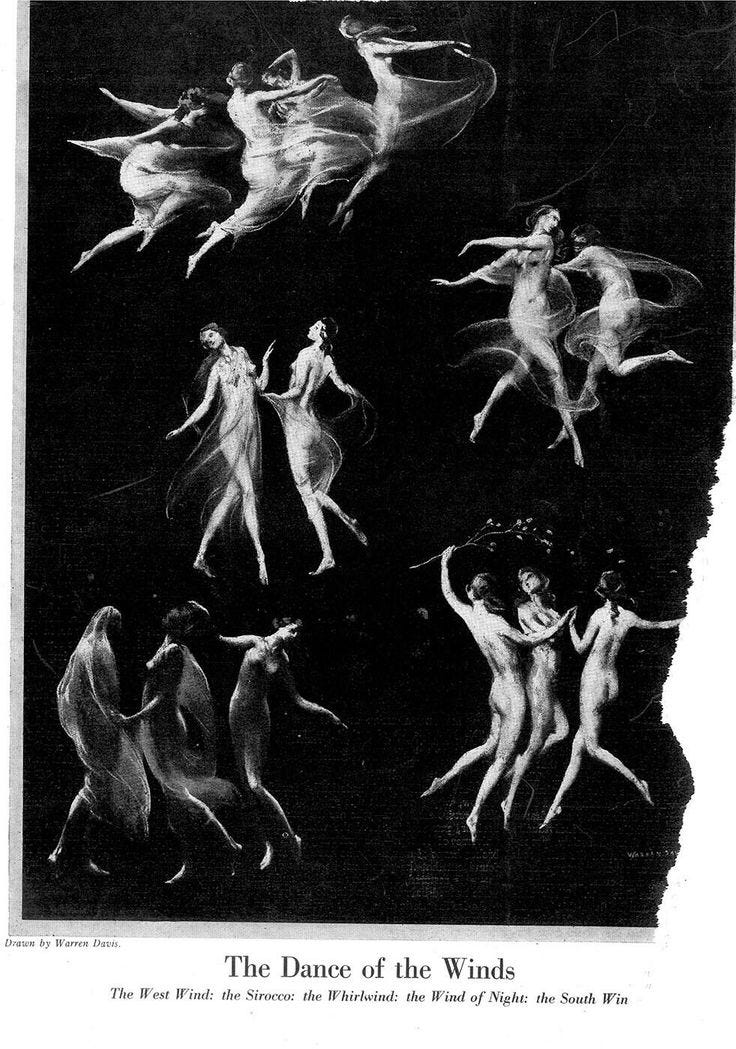

‘Dancing as if language had surrendered to movement—as if this ritual, this wordless ceremony, was now the way to speak, to whisper private and sacred things, to be in touch with some otherness. Dancing as if the very heart of life and all its hopes might be found in those assuaging notes and those hushed rhythms and in those silent and hypnotic movements. Dancing as if language no longer existed because words were no longer necessary…’

— Brian Friel, Dancing at Lughnasa

Light and Might

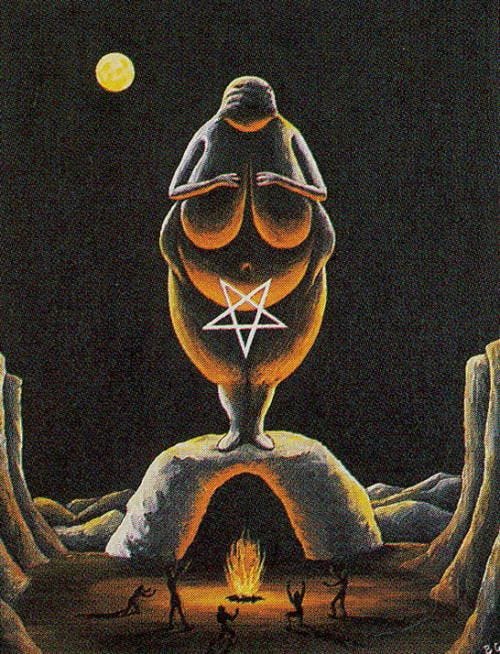

Lughnasa inherits its name from the Samildánach god, Lugh, who is a master of all the arts. From poet and smith to healer and harpist, he is the most skilled of all the gods. Lugh established the festivities of Lughnasa in honour of his foster mother, the goddess Tailtiu, who, with her supernatural might, felled the great forests of Ireland to make way for our transition to agriculture. When her feat was done, she lay down and died of exhaustion.

‘Great that deed that was done with the axe's help by Tailtiu, the reclaiming of meadowland from the even wood by Tailtiu daughter of Mag Mór [means ‘Great Plain’]… Her heart burst in her body from the strain beneath her royal vest; not wholesome, truly, is a face like the coal, for the sake of woods or pride of timber.’

— From the Dindshenchas, ‘Lore of Places’, a compilation of the mythology and history of place that began in the early medieval period

Here, we witness the death of a Great Mother, the Goddess of Vegetation, as a ‘necessary’ sacrifice for the evolution of human agriculture. There’s much to say on this… but I also see something else here resonant with my own life this Lughnasa: the toil of creativity.

In my creative process, Lugh symbolises imbas, the vision and wisdom that illuminate, the spark of imagination that feels like a divine gift. I love this felt sense of creativity; it’s like dancing with the cosmos, reaching out to grasp the darkness, to catch the stars that lie beyond words so I can bring them into language or whatever form they demand of me. It feels like being at the very heartbeat of life while transcending its known bounds.

As invigorating as lovely Lugh’s energy is, I also need Tailtiu or I’d never make it to the end of a creative project. She is the foster mother who makes new land and prepares the creative soil for cultivation. She grafts, and her steady presence sees me through until the end.

Tailtiu’s fosterage is symbolic here as it is a core theme in Irish mythology and reflects the practices of early Irish society. In this tradition, children were fostered by powerful patrons who taught them skills to amplify their natural talents and often their supernatural abilities. A foster parent served as a mentor, and the child became an apprentice. Creativity itself is a process of apprenticeship, involving devotion to our craft over time and the willingness to see it through, even when it requires scrapping our work and starting afresh. Tailtiu is our ally here.

Dancing Against the Tide

On seeing the end product of creative spark and toil, I recently attended the Gate Theatre’s latest production of Dancing at Lughnasa by Irish playwright Brian Friel, a gift from my gorgeous pal, Eimear. First performed on stage in 1990, the play was adapted into a film in 1998 by Pat O’Connor, starring Meryl Streep and other well-known actors. Set in the summer of 1936 in the fictional village of Ballybeg from Baile Beag meaning ‘little town’ in County Donegal, it tells the touching story of the five Mundy sisters—Kate, Maggie, Agnes, Rosie, and Christina—narrated by Christina's son, Michael.

Watching this mesmerising production, I could see the spark of Lugh and the resilience of Tailtiu in the glimpses we catch of these five women’s lives. We meet the sisters during the “pagan” festival of Lughnasa, alive and well in Ballybeg. Despite the stranglehold the Catholic Church has had on Ireland, it has never fully managed to erase our native beliefs in the Otherworld. The pulse, the beat, the drumming, the almost Dionysian ecstasy of the harvest raps on the windows of the Mundy sisters’ little cottage as the women try to resist at the behest of the eldest, Kate, in favour of what is deemed ‘proper’ by the Church. Dance is what ignites the light of Lugh within the women. They have a new wireless, banjaxed as it may be, whose melodies interrupt the sensibilities of society, rousing the women’s bodies into the flow of Lughnasa, into the celebration of life.

Honouring at Lughnasa

Like Tailtiu, these women are deeply connected to the land and symbolise feminine strength and resilience against the patriarchal tides that crash around them. They show Michael the full scope of the feminine life—from the dark mother to the creation mother and all between. Like Tailtiu’s dying wish, her longing for the Óenach Tailtiu—the ‘reunion’ or ‘assembly’ of Tailtiu that Lugh established following her death—the sisters cling to their holy longings for their own lives right until the end of Lughnasa when we leave them. Friel, akin to Lugh, channelled his creativity into honouring his foster mothers. He based Dancing at Lughnasa on his real-life aunties from the Glenties in Co. Donegal and dedicates the play “in memory of those five brave Glenties women.”

And so, in the spirit of Lughnasa, I dedicate this Imbas Dispatch to your imbas—your creative vision that illuminates—but also like Tailtiu and the Mundy sisters, to your toil for your holy longings and your bravery to walk this path. If that’s not something to celebrate, I don’t know what is.

The Silver Apple

This autumn, I'm opening spaces for one-to-one clients in The Silver Apple programme. In Irish mythology, a silver branch adorned with silver or golden apples serves as an invitation to journey to the Otherworld. This invitation often comes with an enchanted fairy woman whose music awakens the mystical within us, compelling us to answer the Call.

The silver branch's gift is its endless sustenance. The apple replenishes itself infinitely when consumed in the spirit of reciprocity—a principle that resonates at the core of our mythology and folklore. For those with a genuine creative heart, the Otherworld ensures an endless supply of nourishment.

Inspired by this myth, The Silver Apple programme aims to deepen your connection with the Celtic Otherworld, inviting ancestral wisdom into your life to enrich your creativity, well-being, and sense of belonging. Here, you'll nurture your own silver apple tree and witness its glorious blooming.

I have a limited number of spaces available. If you're intrigued and wish to learn more, please see the link below.

Wishing you a bountiful Lúnasa! 🌾

Croí isteach,

Jen x